A champion for Black musicians and Black rights, Archie Alleyne (1933–2015) is recognized as one of Canada's premier drummers and legendary jazz artists.

One of the first Black drummers heard in Toronto's Yonge Street clubs during the 1950s and 1960s, Alleyne fought systemic racism and discrimination throughout his career. A lifelong musician and activist, Alleyne was named a Member of the Order of Canada in 2012, only three years before his death.

Kensington Market Kid

Born during the Great Depression in 1933, Archibald Alexander Alleyne grew up in Kensington Market, a densely populated neighbourhood home to many Jewish families and members of the city’s small Black community. According to the 1931 Canadian Census, taken only two years before Archie was born, only 2 out of every 1,000 residents in Ontario were Black.

Archie’s father was a railway porter, a profession for many Black men in Ontario at that time. One of Archie’s first musical experiments involved taking his father’s railway whisk broom and scratching it over a magazine cover, or tapping a pair of sticks to try out new rhythms. Primarily self-taught, he soon replaced these make-shift instruments with a snare drum and ride cymbal, playing in church basements and legion halls.

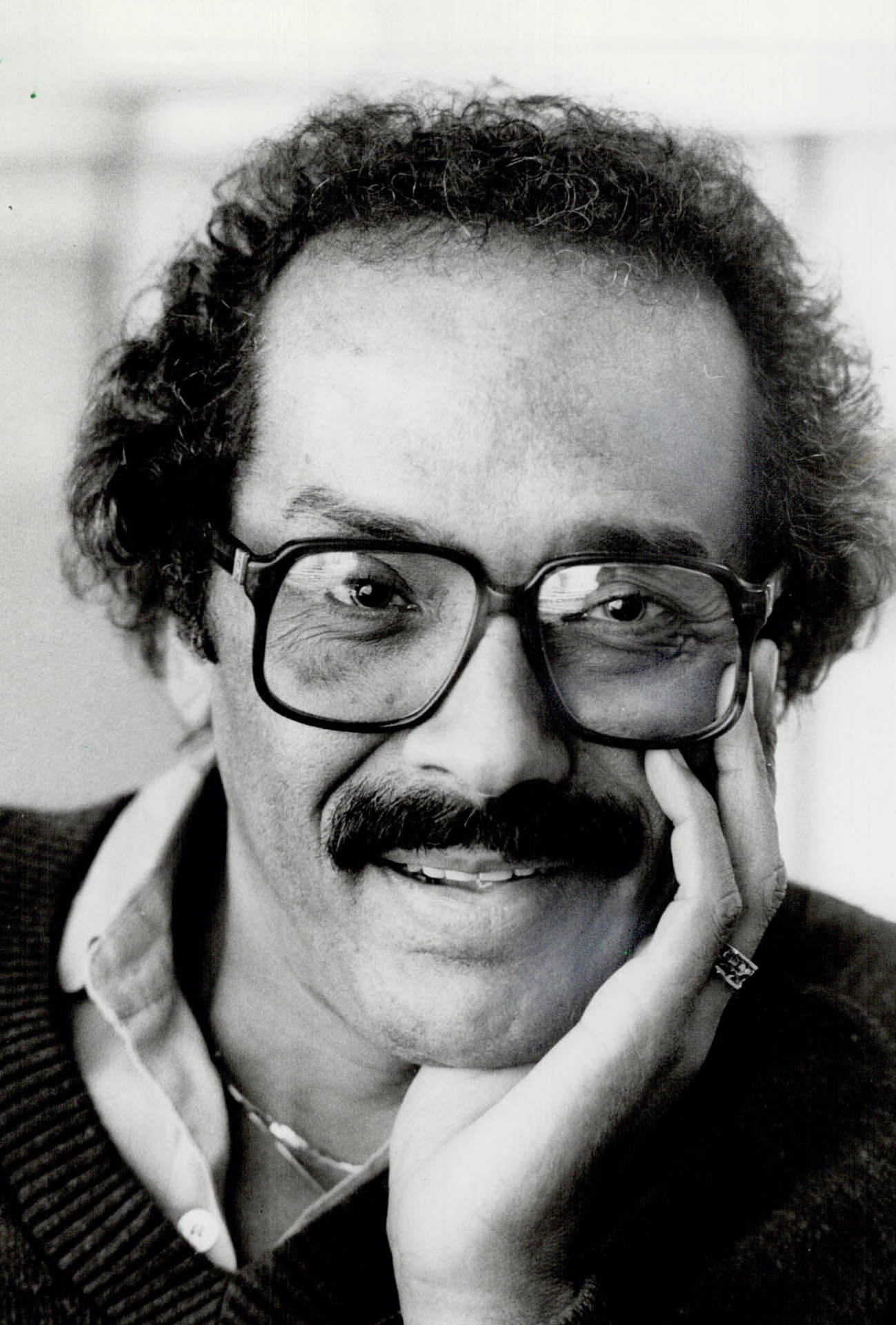

Archie Alleyne in 1983, the year that he protested discriminatory funding practices by the Canada Council for the Arts.

Photo by Boris Spremo, courtesy of the Toronto Star Photo Archives

Without the past, there is no future.

— Archie Alleyne

Breaking Barriers

Success came quickly, but so too did the social and cultural obstacles. During the 1940s, Black artists were largely not invited to play in popular clubs in downtown Toronto.

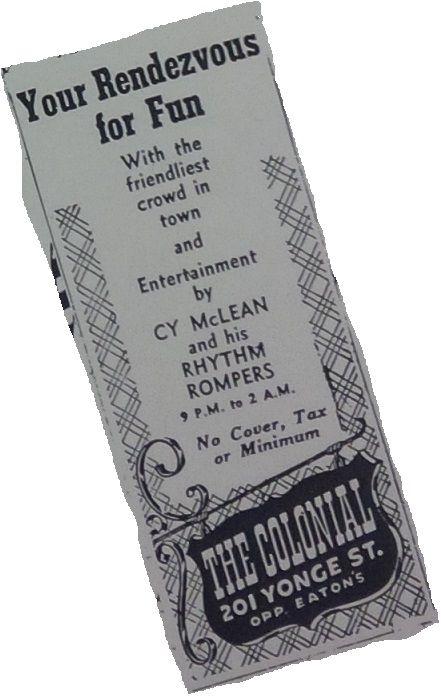

During the late 1940s, swing musician Cy McLean and his Rhythm Rompers band were among the few Black musicians booked to play venues on Yonge Street, like the Colonial Tavern.

Toronto Star advertisement for Cy McLean and his Rhythm Rompers at the Colonial. Toronto Star, April 22, 1947

Cy McLean and his Rhythm Rompers playing at the Colonial, circa 1947. Courtesy of Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collection, Archie Alleyne Fonds

Watch: Racism in Toronto's Jazz Scene

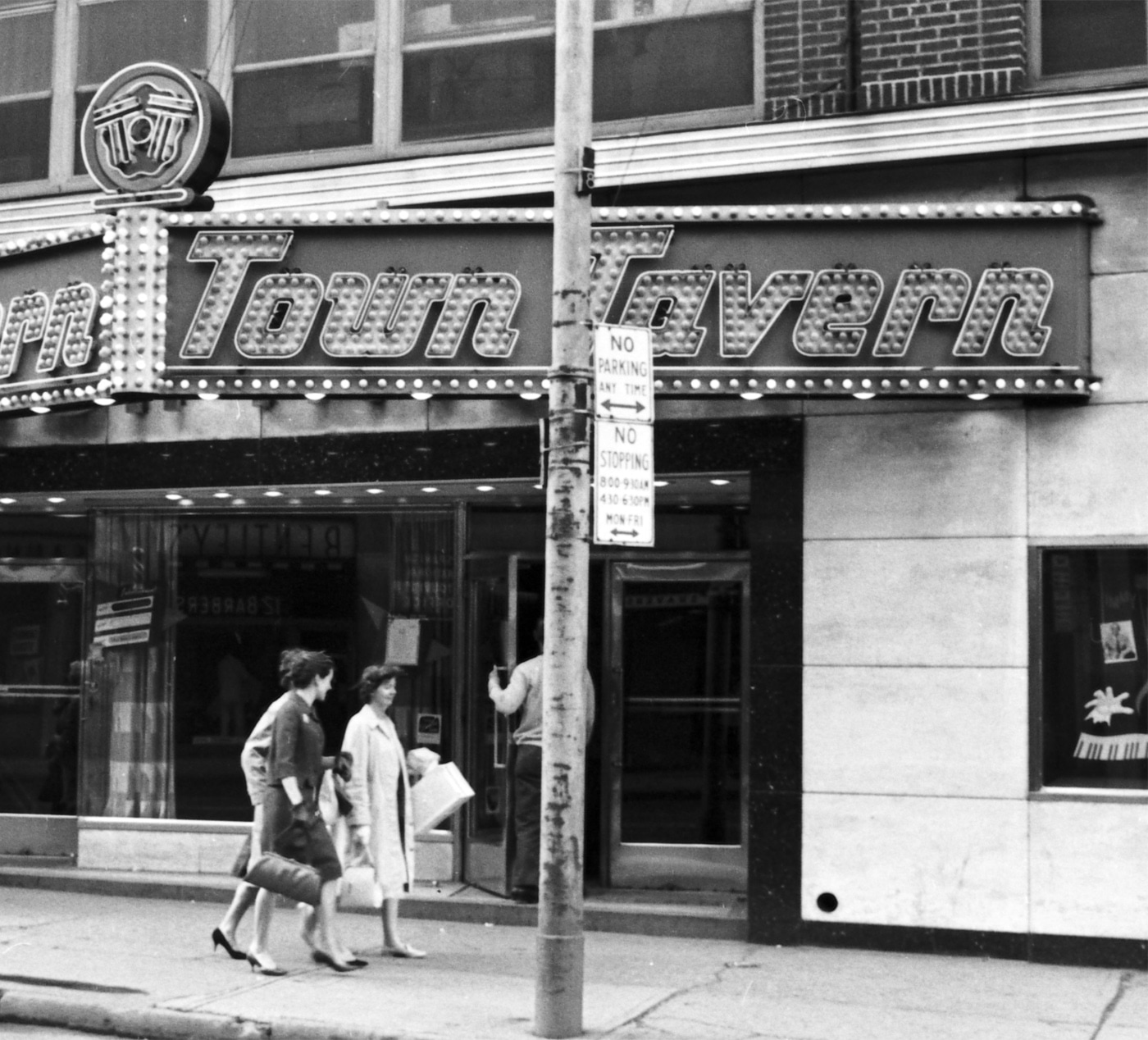

Resident drummer at the Town Tavern and the Colonial Tavern for several years, Archie Alleyne was one of the few Black musicians playing on Yonge Street. He discusses the time he wasn't hired for a job because of his race, what it was like to be a Black artist on Yonge Street, as well as the legacy left by previous Black musicians in Toronto, such as Cy McLean.

This online exhibition uses third-party applications including Spotify and YouTube. Check with your organization’s web administrator if you are unable to access content from these channels in the exhibition.

From "Tuning Up", Heritage Toronto's 2014 Black History Month concert and panel discussion. Recorded for Heritage Toronto

View Transcript(Panel sits before audience in St. Lawrence Hall's Great Hall. Archie Alleyne speaks into a mic while the other three panelists and the moderator, Eroll Nazareth, listen. Alternates between close ups of Alleyne and wide shot of whole panel.)

[Applause]

Archie Alleyne: Frankly, there was a lot of prejudice here, there was a lot of discrimination. I was one of the first Black musicians to break, infiltrate --

Errol Nazareth: I like that word a lot, say it again.

Archie: –Infiltrate the white establishment.

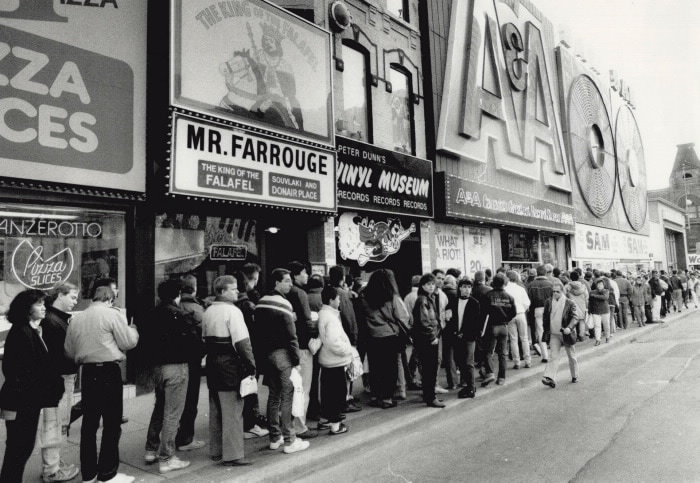

I was resident drummer at the Town Tavern and at the Colonial Tavern for 13 years. But prior to that there weren't any Black musicians on Yonge Street in any of the clubs. The first musicians to break that barrier was Cy McLean, who's from Nova Scotia. And he went into the Colonial Tavern in 1947, and after that, and up and down Yonge Street, there was a number of clubs starting from up on Bloor Street all the way down to Queen Street. Lots of clubs, the Zanzibar and all that.

And of course the Blackburns were taking over. That's when the R and B scene started, you know. The jazz scene, it was not easy. I got a lot of. I was called a lot of names other than what my mother named me. There weren't very many. A lot of the community – the Black community – didn't come out to the clubs, because they never felt welcome. It's a shame, but that's the way it went. But there we were.

We had our own clubs within our communities, like Spadina and Dundas. I was born on Queen Street next to the Cameron Hotel in the building that is there. So I know the area quite well, Kensington Market was my playground. I still go down there and my daughters are down there. They live down there still. So, the scene, I did what they called the cross-over. I left the Spadina-Dundas area because I wanted to be a musician and wanted to make my living as a musician, and in order to do that I had to make the cross-over from Spadina and Dundas and go to Bloor and Avenue Road and Bloor, where the after-hours clubs started.

So I started infiltrated the after-hours clubs and all that and kept going. That was part of my schooling, that was how I learned how to play. It wasn't easy at times, but finally. Even with the Toronto Musicians Association, Cy McLean and his band members were the first ones allowed in the Toronto Musicians Association. No Blacks were allowed in the association at that time.

Errol: Wow.

Archie: And what they did was they, was make the fee so high that no one could afford it, or you would have to go through a test of reading music. And most of the musicians -- some of them read and some of them didn't.

Now, I'll give you a little story about the white-blackness. I had a friend of mine, his name was Mort Ross. He was a saxophone player, he was a Jewish fellow. And he said "Arch, there's an ad in the paper here." And this was for a summer engagement. And summer engagements were a great part of a musicians livelihood, because you could go away for a couple of months and work all summer in one of the resorts, you get paid, you eat, you sleep, and you have a good time. And so he said, "this guy wants a drummer and he wants a saxophone player, let's go audition." So, we called the guy up, and we went, we auditioned, and we left and Mort called me about two hours later and said, "Archie, I got the job", he said. "But, he's a little afraid about taking you up to the Muskoka. Because he's afraid about how they're going to accept a Black person up there."

I said, "well, that's okay. I'm going to call the union, and I'm going to report him." So I called the union, Norm Harris was the secretary at the time, and Walter Murdoch was the president, who was pretty well a racist at that time. But I went down, saw Norm Harris, and he called the chap down that had put the ad in the paper, sat us both down, and right away he said "why can't you take Archie up there?" And he said "well, I don't know how they'd accept a Black musician up there." He said, "well, I'll tell you this. If Archie doesn't go, there's no job. Nobody is going. I'm going to cancel it."

So he said, "Archie do you want to go?" And I said, "No" because I just got offered another job, out in Muskoka, a mile away for two months, and this was with Graham Poppy, one of the fine trumpet players in the city, so I think I'll take that job. And that job lasted for three summers, you know.

So that's just one of the incidents that went on.

[Applause]

Click here to travel through time

The Town Tavern, Queen Street East, in the 1950s and the same location seen in 2019.

Courtesy of York University Libraries, Clara Thomas Archives and Special Collections, Toronto Telegram fonds

Photo by Vik Pahwa, 2019

The Town Tavern

Archie Alleyne followed in the footsteps of great swing and jazz legends like Cy McLean, becoming the resident drummer at both the Town Tavern and the Le Coq D’Or on the bustling Yonge Street strip during the 1950s and 1960s.

Much like the coffeehouses of Yorkville, many of the Yonge Street clubs were so close to one another that you could go in-between sets and listen to another band playing at a neighbouring tavern. Many of these live music spaces closed by the 1980s, replaced by other shops and restaurants in Toronto's busy downtown core.

Opened in 1949 as a theatre restaurant, club owner Sam Berger turned the Town Tavern into a full-time jazz venue in 1955 at the suggestion of legendary Canadian pianist, Oscar Peterson.

Known for his improvisational skills developed through swing and bebop styles, Archie became the drummer of choice, playing for international touring jazz luminaries. He played with singing sensation Billie Holiday, saxophonist Ben Webster, trumpeter Chet Baker, singer Nina Simone, and hundreds of other jazz musicians.

Archie Alleyne accompanying Billie Holiday at the Town Tavern, August 10, 1957.

Photo by Erik Christensen, courtesy of the artist's estate

Listen: For You, E.

What I am trying to do is to take the jazz music we are playing and give it a little more sophistication, take it out of the basement and bring it to the people…

I’d like to have people dance to our music instead of just sitting here with their eyes closed, snapping their fingers.— Archie Alleyne

This online exhibition uses third-party applications including Spotify and YouTube. Check with your organization’s web administrator if you are unable to access content from these channels in the exhibition.

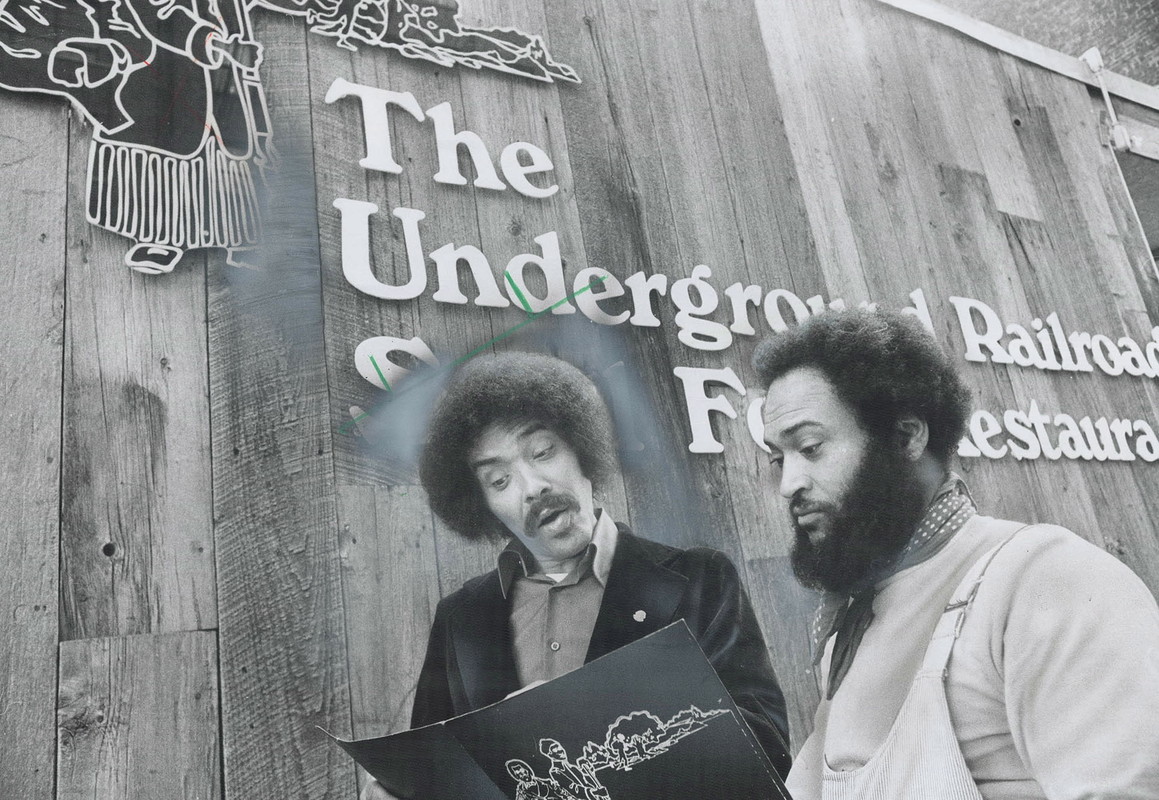

Archie Alleyne (left) and a friend stand outside The Underground Railroad Soul Food Restaurant, Toronto, 1973.

Photograph by Jeff Goode, courtesy of Toronto Star Photo Archives

The Underground Railroad

Archie took a break from keeping the beat in 1967, after a serious car accident left him unable to perform. With three friends, he opened The Underground Railroad Tavern, a soul food restaurant that served southern food and hosted jazz performances.

It was considered the first of its kind in Toronto.

Our aim is to put more colour in Toronto.

— Howard Matthews, co-owner of The Underground Railroad Tavern, 1969.

Watch: Archie and Kollage

Watch Archie Alleyne talk about his work with his Toronto jazz ensemble, Kollage, which he formed in 2001. Before his death in 2015, the group played regular gigs at The Rex, a prominent jazz venue on Toronto's Queen Street West. As he says, "It's not what we play, it's how we play it."

This online exhibition uses third-party applications including Spotify and YouTube. Check with your organization’s web administrator if you are unable to access content from these channels in the exhibition.

Courtesy of Fairfield Films.

View Transcript(Close up of Archie Alleyne speaking. A slideshow archival photos of his band performing. Return to close up of Alleyne. Shots of signs for The Rex Jazz and Blues Bar. Interior of The Rex with scene of people socializing in bar. Exterior of the Rex. Return to Alleyne close up. Shots of band performing. Return to Alleyne close up. Jazz music plays over montage shots of interior of The Rex with shots of Alleyne's band Kollage performing there ending with applause. Fade to black then Fairfield Films logo.)

Transcript

Archie Alleyne: It's not what we play, it's how we play it. We're one of the most energetic bands that we have here in the city. We put a lot of energy into it. We don't sit up there and look at a lot of sheet music staring us in the face. We learn the tunes, and try to do them off the top of our heads. And half the times recording with Dougie, we have to get a clip on microphone because he's all over the place.

And so are the other guys, you don't just stand there like a mannequin. There's a lot of energy put into the band, that's what makes the music so exciting. Thank goodness for the Rex and for Tom and Bob Ross, because they are giving all the young musicians the opportunity to come out and express themselves and to improvise on their instruments.

Dougie came back from LA, he'd been down there for a number years in Chicago, he had to move out of Toronto because there's not enough work for him. But he came back and said "we gotta get a band together, and we gotta get a Black band, because there's not enough around here." They're here, but they're not getting the work.

So, I just kept hunting, I went to Humber College and found some young Black musicians. I went and got...my first pianist was Michael Shan out of York University, who s now with Matt Dusk, he's his musical director now with another chap, Larnell Lewis, who is a fantastic drummer.

So, I just kept looking for Black musicians, bring the band out, and to represent my community, basically because the origins of jazz are in the Black community, so we needed some representatives from that community to play that music. So that's how we started.

Archie Alleyne playing the drums in 2011.

Photo by Greg Gooding

Activism & Mentorship

An activist in the Toronto music scene, Archie lobbied for Black musician’s rights and called out the Canada Council of the Arts in 1982 when they excluded jazz musicians from their funding. Two years later, he led a significant lobby for Black musicians to be included in the Toronto Jazz Festival.

At the turn of the last century, Archie co-founded two jazz ensembles: Evolution of Jazz, a nine-piece ensemble in which he mentored recent graduates, and Kollage, a six-piece ensemble which focused on the hard bop style of the 1950s; the latter became one of the busiest jazz bands in the country.

Since 2003, the Archie Alleyne Scholarship Fund had provided 73 scholarships to support emerging jazz artists. In recognition of his contributions to Canadian jazz heritage and his commitment to youth mentorship, he was made a Member of the Order of Canada. Archie continued to be involved with Toronto’s music scene until his death in 2015.

Listen: Archie Alleyne's Impact

Listen to fellow Toronto jazz musician Brooke Blackburn speak about the hardships, racism and discrimination that Black musicians, including Archie Alleyne, experienced in Toronto throughout the past 65 years.

This online exhibition uses third-party applications including Spotify and YouTube. Check with your organization’s web administrator if you are unable to access content from these channels in the exhibition.

Recorded for Heritage Toronto, 2019.

View TranscriptBrooke Blackburn: Cy McClean who had a big big band, you know and Archie was I believe was one of the first Black artists allowed to play certain clubs in the city that my father told me about and…and I knew Archie. And…you can't…you could never really really understand how much importance that these people did, you know had for you as a Black musician in Toronto?

Like just because I’d heard so many stories, you know and still hear stories to this day from my father and my friends….or my father's friends that that grew up playing in the city back in the 50s and 60s who, I started playing with them in the 70s, you know, and it was just so…it's such an impact.

So as far as the…the racial aspect of it, they literally opened the doors for us because there was a colour barrier no matter what everybody thinks. There is and there still is a colour barrier, but definitely at that time when they started out. And then I'm sure there was people that opened the doors for them too, you know what I mean?

But Cy and Archie really really opened the doors for many and my father, he played on Yonge Street. And it was hard core. But he had…the black musicians loved playing Yonge Street: the Colonial and the Coq d’Or and certain places on Yonge Street because it's just like when the…when the second world war, when the Black…Black army people came in and the navy…and they all went to Europe they felt like people, you know, and they come back to the United States, and they couldn’t even stay in the same hotel as a white person.

Yet they're fighting with them in the trenches. So it's like that and Toronto was still open much more open than the States, but there was still limitations. Like I say Archie, was the first Black musician at a certain level.

Dive Deeper

Archie Alleyne with Sheldon Taylor and Eric Alister. Colour Me Jazz: The Archie Alleyne Story. Toronto: Kollage Productions, 2015.